Module 10: An introduction to environmental rights as an advocacy framework

Environmental rights are “people-centric” in that they are related to the health and well-being of people and future generations.

The “circularity gap” is widening

The special relationship between us and the planet requires urgent and effective action. Working towards a circular economy of digital devices is an important part of the action that is needed from us. If you are reading this, you are an agent of change.

The main existential threats that humanity and the planet are facing are inequality (lack of income, lack of any critical resources, the so-called “poverty line”), pollution, and biodiversity loss (an excess environmental footprint, or what we call “overshooting”). The risks are social and ecological collapse. Opportunities lie in finding ways to mitigate and redress these threats, including through social and environmental good being embedded in what we do and in the laws we make to govern ourselves.

In a report to the World Bank more than a decade ago, Elinor Ostrom said:

Efforts to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions are a classic collective action problem that is best addressed at multiple scales and levels. [...] Building a strong commitment to find ways of reducing individual emissions is an important element for coping with this problem.[1]

This is also about what we as individuals can do, the unequal circumstances and relationships among people, the role of money, property, power, education, policy and environmental justice, and the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, with a fair distribution of environmental benefits and burdens.

Fast forward. Today there is bad news:

[In 2020], the global economy [was] only 8.6% circular – just two years ago it was 9.1%. The global circularity gap is widening. There are reasons for this negative trend, but the result remains the same: the news is not just bad, it is worse. The negative trend overall can be explained by three related, underlying trends: high rates of extraction; ongoing stock build-up; plus, low levels of end-of-use processing and cycling. These trends are embedded deep within the “take-make-waste” tradition of the linear economy – the problems are hardwired. As such, the outlook to close the circularity gap looks bleak under the dead hand of business as usual. We desperately need transformative and correctional solutions; change is a must.[2]

Environmental rights are about the planet and people

We need to redirect global society to a more sustainable future with equity and environmental sustainability as a priority. According to McAlpine et al., “Transformational change in societal values needs to occur at three levels by: (1) being responsible and ethical in our dealings with other people and our environment; (2) better integrating ourselves into our communities; and (3) reconnecting with and valuing nature.”[3] Values such as personal integrity, compassion, strong and interconnected communities, globally responsible citizens with global awareness, and mutual aid and cooperation, ultimately help to reduce the human ecological footprint on the planet.

Respecting people has several dimensions, and a rights-based approach focuses on human equity, ensuring good or desirable actions or outcomes and preventing those that are undesirable for everyone. These rights need to be enacted in a legal system or ensured through an equivalent mechanism, such as industry ethical codes of conduct. Environmental rights are “people-centric”: they are related to the health and well-being of people and future generations.

People-centric environmental rights can be viewed from three perspectives:

- Civil and political rights, which empower people with access to environmental information, judicial remedies and politic processes (as outlined in the Aarhus Convention). We can think of this as a "greening" of human rights to prevent the harmful impact of environmental degradation and destruction on individual humans. Civil and political rights also contain collective rights.

- Economic or social rights, which include the right to a healthy environment, but which are vulnerable to competing objectives, such as the right to economic development (as outlined in Agenda 21). Economic and social rights can also be seen as collective rights.

- Collective or solidarity rights, which give communities (“peoples”) rather than individuals a right to determine how their environment and natural resources should be protected and managed, such as through the protection of minority cultures and Indigenous people. An example of collective rights is the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights gives all peoples the right to freely dispose of their natural resources, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights protects minority cultures and Indigenous people and their natural resources.

|

Environmental justice and human rights We have to face global environmental inequality, which refers to "the expression of an environmental burden that would be borne primarily by disadvantaged and/or minority populations or by territories suffering from a certain poverty and exclusion of these inhabitants."[4] The environmental justice movement focuses on the “fair” distribution of environmental benefits and burdens, as it is evident that exposure to pollution and other environmental risks are unequally distributed by race, class and region, among others. When we translate these aims to humans, we talk about environmental rights defined in terms of human rights: “the right to a healthy environment and its preservation for future generations” (e.g. the Cartagena Declaration).[5] |

|

Agenda 21 and the Sustainable Development Goals Agenda 21 (with the “21” referring to the 21st century) was a result of the Earth Summit held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1992. Agenda 21 is a non-binding action plan of the United Nations with regard to sustainable development. It talks about changing consumption patterns, the conservation and management of resources, and strengthening the role of “major groups” such as Indigenous communities, and outlines diverse means of implementing the actions. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development reaffirmed Agenda 21 and established the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Many of these goals include circular principles, specifically Goal 12 on “Responsible consumption and production”. |

|

Environmental rights and the human rights framework Both civil and political rights and economic, social and cultural rights are important to environmental rights. Economic, social and cultural rights are generally concerned with encouraging governments to pursue policies which create conditions for individuals, or in some cases groups, to develop to their full potential. Civil and political rights are the rights that protect an individual’s freedom from infringement by governments, social organisations and private individuals. As environmental inequality is usually the result of conflicting interests, civil and political rights are important in securing the health and well-being of an affected population. |

|

Aarhus Convention The reference instrument for global environmental justice is the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters, more commonly known as the Aarhus Convention, which entered into force in 2001. It promotes effective public engagement in environmental decision making, and defines procedures for its implementation by public authorities. The Aarhus Convention follows a rights-based approach: the public, both in the present and in future generations, have the right to know and to live in a healthy environment. |

|

Charter of Human Rights and Principles for the Internet The Internet Governance Forum’s Internet Rights and Principles Coalition has developed a Charter of Human Rights and Principles for the Internet that defines the right to development through the internet with two sub-clauses:

4a) Poverty reduction and human development: Information and communication technologies shall be designed, developed and implemented to contribute to sustainable human development and empowerment. 4b) Environmental sustainability: The Internet must be used in a sustainable way. |

|

The Brazilian constitution At the national level, there are many examples of clauses protecting the environment. One example is from the Brazilian constitution. Article 225 establishes the “right to an ecologically balanced environment” and states in paragraph 1 that in order to ensure the effectiveness of this right, it is incumbent upon the government to “control the production, sale and use of techniques, methods or substances which represent a risk to life, the quality of life and the environment,” and to “promote environment education in all school levels and public awareness of the need to preserve the environment,” among other measures. Meanwhile, paragraph 4 states:

The Brazilian Amazonian Forest, the Atlantic Forest, the Serra do Mar, the Pantanal Mato-Grossense and the coastal zone are part of the national patrimony, and they shall be used, as provided by law, under conditions which ensure the preservation of the environment, therein included the use of mineral resources. |

The right to access to environmental information, public participation and justice

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters, known as the Aarhus Convention, was adopted on 25 June 1998 in the Danish city of Aarhus and entered into force on 30 October 2001.

It establishes a number of rights of the public (individuals and their associations) with regard to the environment. The parties to the Convention are required to make the necessary provisions so that public authorities (at national, regional or local level) will contribute to these rights becoming effective.

The three pillars of the Convention are:

- Access to information: Any citizen should have the right to easily access environmental information. Public authorities must provide all the information required and collect and disseminate it in a timely and transparent manner. They can refuse to do this only in particular situations (such as in the interests of national defence).

- Public participation in decision-making: The public must be informed of all relevant projects undertaken by governments, and have the chance to participate during the decision-making and legislative process. This is important because decision makers can take advantage of people's knowledge and expertise. This is an opportunity to improve the quality of the environmental decisions and outcomes and to guarantee procedural legitimacy.

- Access to justice: The public has the right to judicial or administrative recourse procedures in case a party violates or fails to adhere to environmental law and the Convention's principles.

Like the Aarhus Convention in Europe, two decades later, the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, also known as the Escazú Agreement, was reached by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). This represents a commitment by the signatories to promote access to information, public participation and access to judicial remedy in their respective national policies related to the environment.

According to UN Secretary-General António Guterres, who wrote the Foreward to the agreement, “this treaty aims to combat inequality and discrimination and to guarantee the rights of every person to a healthy environment and to sustainable development.” He added, “In so doing, it devotes particular attention to persons and groups in vulnerable situations, and places equality at the core of sustainable development.”[6]

For her part, ECLAC Executive Secretary Alicia Bárcena stressed in the Preface: “The Regional Agreement is a ground-breaking legal instrument for environmental protection, but it is also a human rights treaty.”[7] She goes on to state:

It aims to ensure the right of all persons to have access to information in a timely and appropriate manner, to participate significantly in making the decisions that affect their lives and their environment, and to access justice when those rights have been infringed. The treaty recognizes the rights of all individuals, provides measures to facilitate their exercise and, most importantly, establishes mechanisms to render them effective.[8]

The text of the agreement emphasises that “environmental information” includes information related to “environmental risks, and any possible adverse impacts affecting or likely to affect the environment and health.”[9]

Environmental justice in the circular economy

In the context of the circular economy of digital devices, environmental justice affects different stakeholders directly in each of the circular processes.

The circular economy is a declaration of interdependence: my computer or phone is not just mine, it is ours, for two reasons: first, someone else could have used it before me, or could use it after me, and second, it depends on and affects nature.

According to the Charter of Human Rights and Principles for the Internet developed by the Internet Governance Forum’s Internet Rights and Principles Coalition, digital devices need to be designed, developed and used in a way that contributes to sustainable human development and empowerment (as per sub-clause 4a), and the internet must be used in a sustainable way (sub-clause 4b).

The Aarhus Convention offers procedures for access to environmental information, which with regard to digital devices means information about materials, design, usage, maintenance, repair, their parts, and ways to dismantle and recycle them. This can be extended to specifications, programming, firmware and software to allow maintenance and continued use. Especially when manufacturers decide to stop maintenance, this will allow third parties to do so.

Information on raw materials, which includes the many negative effects they can entail, especially for marginalised and Indigenous communities, deserves special attention and requires environmental responsibility from device manufacturers to monitor and report on the social and environmental implications of their supply chain. Manufacturers also need to provide information on their extended producer responsibility, regarding the “reverse supply chain” when devices are no longer used and have to be recycled and materials recovered. Access to this information is central to the idea behind “product information sheets”, also called “digital product passports”,[10] and the production of verifiable and public data about devices and their life span. The eReuse case study in Module 1 shows how open datasets[11] help citizens and organisations contribute to decision making, and can assist purchasing decisions based on actual durability, repairability and recyclability statistics.

The Aarhus Convention also offers procedures for public participation in decision making. Citizens should be informed and allowed to participate during the decision-making and legislative processes for laws and recommendations related to key circular processes. These include ecodesign, which relates to durability and repairability, green public procurement, taxation of repair and reuse, rules for depreciation of material assets, recycling and e-waste processing, as well as consumer rights and labour rights in the electronics industry.

Finally, the Aarhus convention offers procedures for access to justice, for citizens and NGOs, when a party violates or fails to adhere to environmental law and the Convention's principles of access to environmental information or public participation.

Universal access to digital devices translates into people-centric rights such as the right to repair,[12] the right to know,[13] the right to transfer (sell or donate for reuse), and the right to have a user device to be able to participate in society or education through digital means. Of course, these rights come with responsibilities: environmental to minimise manufacturing and e-waste, and socioeconomic to ensure our usage facilitates universal access to devices for everyone.

Nature as a global commons

Nature is a limited critical resource system that impacts and belongs to all of us. Another way of putting it is that it is a “global commons”. This means we collectively need to manage and limit it as a global commons to preserve it as a critical resource for life as we know it. Thinking of nature as a global commons also means we can think of natural resources as global public goods or services.

Public goods are intended to be enjoyed by all people. Public goods are “non-rival”, which means use by one person should not prevent use by another, but this is only an ideal. Because we are already living beyond the environmental limits, some uses may rival with others. Therefore, to make sure everyone has the right to nature and its benefits as global public goods or services, nature has to be managed and governed as a global commons, with rules and limits to prevent its misuse, and to maximise its benefits and services within environmental limits.

This would enable litigants and NGOs to challenge environmentally destructive or unsustainable development on public interest grounds. It would give environmental concerns greater weight in competition with other rights.

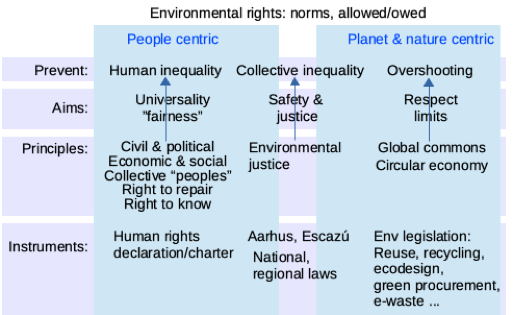

Figure 15 The framework of environmental rights: Individual, collective and planet-centric

Figure 15 illustrates the complete framework of environmental rights. These define and regulate the relationship between people and the planet using different instruments, and are driven by a set of principles aimed at preventing us from living beyond social and planetary limits.

APC’s environmental justice priorities

APC has identified four cross-cutting priorities when it comes to environmental justice:

- First, centring the sovereignty and rights of Indigenous peoples and traditional communities in our work to contribute to environmental justice and sustainability. Indigenous land defenders and traditional communities are on the frontlines of collective action and activism for environmental justice and preservation of the Earth, and experience ongoing threats to their safety, health and sovereignty. Indigenous data sovereignty includes the rights of Indigenous people to govern the collection, ownership and application of data.

- Second, supporting digital safety and care among environmental movements, rooted in communities of practice. Holistic digital safety and care are growing priorities for environmental justice movements. The global COVID-19 pandemic has forced many organisations to adapt and work with digital technologies. Yet many environmental organisations and movements do not have digital safety policies and practices in place.

- Third, working towards social and economic justice and digital inclusion. APC members are developing and deepening initiatives to repair, refurbish and redistribute digital technologies, working closely with local social enterprises. Growing demands for remote education and work mean that the repair and reuse of digital devices has become crucial for digital inclusion. At the same time, APC is working with partners to understand the impacts of extractivism and manufacturing on the health of ecosystems and human labour.

- Fourth, responding to environmental racism in the development and governance of digital technologies. APC recognises that the burden of environmental destruction and pollution falls disproportionately on communities that experience discrimination, marginalisation and exclusion.

Footnotes

[1] Ostrom, E. (2009). A Polycentric Approach for Coping with Climate Change. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5095. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1494833

[2] Circular Economy. (2020). The Circularity Gap Report 2020. https://www.circularity-gap.world/2020

[3] McAlpine, C. A., Seabrook, L. M., Ryan, J. G., Feeney, B. J., Ripple, W. J., Ehrlich, A. H., & Ehrlich, P. R. (2015). Transformational change: creating a safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society, 20(1). http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269773

[4] Gobert, J. (2019, 2 July). Environmental inequalities. Encyclopedia of the Environment. https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/society/environmental-inequalities

[5] Friends of the Earth International. (2003, 24 September). The Cartagena Declaration. https://www.foei.org/news/the-cartagena-declaration

[6] Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. (2018). Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/43583/1/S1800428_en.pdf

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] European Commission. (2021, 11 May). EU countries commit to leading the green digital transformation. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/eu-countries-commit-leading-green-digital-transformation

[11] Franquesa, D., & Navarro, L. (2020). eReuse datasets, 2013-10-08 to 2019-06-03 with 8458 observations of desktop and laptop computers with up to 192 features each. https://dsg.ac.upc.edu/ereuse-dataset

[12] See also: https://www.repair.org

[13] For example, the right to know details about devices, such as durability, before purchasing, as well as access to manuals for maintenance, materials and data sheets for dismantling and recycling, etc.

No Comments