Module 11: Challenges and ways forward for policy action – awareness, mining, design, manufacturing and procurement

Formal and informal mining are in desperate need of regulation, while the design and manufacturing of devices need to ensure that materials are sourced and used in such a way that environmental, labour and people’s rights are protected. Public procurement can leverage economic power to force change for the better in the tech industry.

Goals, responsibilities and procedures

The high-level policy action analyses in this module and in Module 12 have been developed from the perspective of “sustainability” and “circularity”. An in-depth evaluation of existing, required or recommended policy and regulation mechanisms is unfeasible. Policies and regulations depend on local conditions and challenges that may not be the same in all countries or regions. Global sustainability objectives need to be translated and adapted to local ways, creating local incentives and local benefits to ensure effective collective action towards minimising environmental and social impacts.[1] The suggestions for policy action have to be checked and carefully transposed to local conditions, as some effects cannot be predicted.

In general, policy, legislation and regulation tend to have the following elements that need to be clearly defined:

- The goals and targets of the policy, legislation or regulation.

- Roles and distribution of responsibilities and obligations for each role.

- Procedures to perform the associated tasks:

- The permitting (certification, licensing, etc.) of actors so that they qualify to perform the tasks.

- The required reporting and controls or auditing to verify compliance of the tasks performed and to assess the impacts on people and the environment.

We will discuss the different challenges and ways forward for policy action in these terms.

Public awareness

Goal and targets

The transition from a linear to a circular economy can help ensure that humanity achieves common social aims while staying within ecological limits, in line with the targets set out in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and illustrated by the “doughnut diagram” of “the safe and just space for humanity”[2] described in Module 2.

Responsibilities

Public institutions, at the local and global level, have a responsibility to raise individual and collective awareness about this transition, ensuring that it happens at the right pace, helping citizens and organisations determine their commitments – and supporting efforts to implement them – and informing them about their achievements as a result of the collective action.

Procedures

Public education programmes can help citizens realise the environmental and social benefits of circular models, the unfeasibility of the “take-make-waste” linear model, and the rights and opportunities for citizens when it comes to circular business models. Programmes can use community communication strategies and the language of young people to help citizens become part of the solution (e.g. the work of the social cooperative INSIEME in Vicenza, Italy).[3]

Transparency and accountability on the part of governments and regulatory agencies about the environmental impact of digital devices are necessary. Public agencies need to respond to the rights of citizens to know about the environmental impact and social responsibility involved in end-of-use devices. This includes information around what buyers do with their devices and what manufacturers and recyclers do with the devices they collect for recycling. There is a need for proper reporting on the extent to which integrated waste management systems have been established. Publicly accessible data about devices is key to understand, report on and control or audit the circularity of digital devices.

Researching the circular economy and creating public datasets about the durability, repairability, reusability and recyclability of digital devices can help speed up adoption and optimisation of the benefits of circular practices and models. There is a need for open data on accountability and for audits of the durability and environmental impacts of devices, and to establish mechanisms such as the EU’s “product passports”.[4] Open data about the real durability of devices will help consumers make informed decisions and encourage them to buy more durable devices.[5]

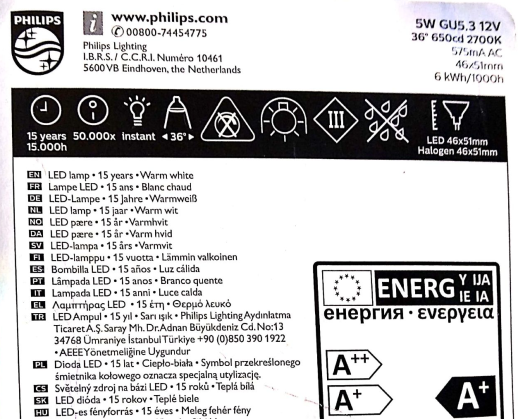

Public awareness can lead to a push for new regulations that require manufacturers to include product details such as those shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16: An example of an information label for an LED lightbulb, with expected durability and consumption information. Similar labels, applied to digital devices, can help consumers make choices with circularity in mind.

Mining and raw material acquisition

Goal and targets

Under a circular model, the acquisition of raw materials requires us to minimise the amount and impact of primary raw materials extracted from the Earth, and maximise the use of a fraction of secondary materials, as resources recovered from the recycling of previous devices. As it stands now, mining is too far away from being a “clean” economy, both with respect to people and the planet.

One of the key policy challenges is that informal mining is often “illegal”, has devastating negative consequences on people, local communities and their territories, is embroiled in armed conflicts, and results in human rights abuses and the degradation of nature. The informal recycling of e-waste can result in mafia-like controls of informal recyclers, human rights abuses and the exposure of recyclers to toxic substances present in e-waste.

An end to bad industry and informal mining and recycling practices implies external regulation and self-regulation.

Responsibilities

Governments have the responsibility to monitor and restrict the way in which mining companies conduct their operations and where they mine, including the impact that their activities might have on local communities. The proper treatment of mining waste that frequently pollutes natural resources is a critical part of this regulation. International mining companies need to be forced to adhere to laws with respect to the human rights violations that may occur in their operations.

Governments also have a responsibility to enact laws that prohibit unregulated and inhumane mining activities, and to attend to the socioeconomic needs of communities that might benefit from illegal mining. Human rights abuses, including gender-based violence and the violation of children’s rights, that occur in artisanal mining need immediate attention and eradication.

Governments and businesses have a responsibility to incorporate informal e-waste recycling into the recycling value chain, in a safe and responsible way.

Procedures

Only detailed transparency, accountability and audits with public scrutiny and strong pressure on all actors in the circular economy can help to limit and eradicate poor mining and recycling practices.

Regarding mining companies, we need to find ways to demonstrate to them the need to adapt their development plans to the concept of a circular economy, seeing it as an opportunity to minimise costs and also to increase their competitiveness. While artisanal mining is largely a subsistence activity and results in miserable living and working conditions with no viable alternatives, large mining companies can, in theory, be held more accountable. They have access to experts and indicators and the technical (and other) capacities with which to institute change. It is likely that the only way to achieve effective change is through pressure from markets (downstream demand from investors or manufacturers and indirectly from consumers who demand that certified materials are used in digital products) and from governments (through policy and regulation, although institutional corruption, which is rife in the mining sector, works against this).

Mitigating emissions is not the same as compensating emissions. Public policies should promote mitigation (improving processes) to compensate for the additional cost of business-as-usual that allows petty payments to be made so that a company can continue polluting.

The increase of secondary materials helps circularity. These materials come as scrap from industrial processes or are extracted from end-of-life devices through urban mining. Encouraging this may include mandatory quotas that stipulate a required fraction of recycled materials to be included in new products, imposed by governments on the designers and manufacturers of new products; taxes on material consumption; and traceability and responsibility regarding sources of materials used in production (both in terms of the impact on the environment and on workers).

Informal e-waste recycling needs to be better understood through research and incorporated into the e-waste recycling chain in a responsible and environmentally sound way. This may require education and training and other forms of capacity and infrastructural development, including the provision of protective clothing and the development of safe work spaces.

Design

Goal and targets

Circularity demands durable devices. This requires designing digital devices for a longer life span and better reparability and reusability.

Responsibilities

Governments are responsible for regulating the design of devices bought and sold in their markets. Brands and manufacturers have the corporate responsibility of preventing the negative impact of manufactured devices by means of the consideration of circularity in design, with energy efficiency, repairability, durability, upgradability, reusability and dismantling in mind.

Procedures

Many countries have introduced laws to regulate and facilitate not only the dismantling and recycling of electronics (or the processing of e-waste), but also, more recently, to support the repair and reuse of digital devices. France, for instance, has introduced a repairability index for electronics that allows buyers to make informed purchase decisions.[6]

Design guidelines that focus on circular economy principles (see, for example, European Commission communications COM033-2017,[7] COM614-2015[8] and COM773-2016)[9] can be categorised in Circular Design Guidelines Groups:[10]

- Extending life span: This group includes design guidelines related to promoting the life span and durability of products by adapting their design and studying the possibility of upgrading new versions, or via timeless designs by ensuring the product can be used for as long as possible.

- Disassembling: This includes design guidelines related to the product's structure and access to its components by distinguishing between:

-

- Connectors – includes design guidelines related to connecting systems to facilitate disassembly.

- Product structure – includes design guidelines related to the location of the main parts and components to facilitate their access.

- Product reuse: This group includes design guidelines that enable the product’s complete reuse by facilitating maintenance or cleaning tasks, and the reuse of its components.

- Components reuse: This includes design guidelines with recommendations for facilitating the reuse of the product's components or parts by using standardised components, minimising parts, etc.

- Material recycling: This includes design guidelines that facilitate the identification, separation and recycling of materials.

The UN’s International Telecommunication Union has a standardisation sector (ITU‑T) that has developed a recommendation for an assessment method for circular scoring[11] inspired by these guidelines. This enables the calculation of the circularity score of an information and communications technology (ICT) product. Several manufacturers and governments have agreed to the recommendation.

Right to Repair is a public campaign in Europe (and other regions) which insists on the right to maintain and to make changes to devices. This concept includes good design (to perform, to last, to be repaired, related to the idea of ecodesign); helping consumers to make an informed choice (e.g. manufacturers indicating the degree of repairability with a scoring system, and including an energy label and information on obsolescence and durability); and fair access to repair (e.g. repair instructions and fair access to spare parts). The Repair Association in the United States, repair.org, pursues similar goals to the Right to Repair campaign in Europe, repair.eu.

Good circular policy from brand owners entails offering maintenance and spare parts for as long as a product may be used, or making a product’s hardware and software design information freely available to the public. This includes freely available public information on chips and printed circuit board (PCB) layouts, access to mechanical drawings, schematics and bills of materials, and information about the software that drives the hardware. This would help the community of users willing to extend a product’s use. It would allow for analysis, feedback and the contribution of improvements to the design from the technical community and also facilitate maintenance, repair and upgrades.

Manufacturing

Goal and targets

Manufacturing involves component and part suppliers, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), assembly and distribution. There are multiple companies involved in the process of manufacturing: from manufacturing discrete components, chips, PCBs, or other parts like batteries and displays to the assembly of devices, as well as packaging and transport across the supply chain for distributors and retail sale.

Responsibilities

Governments have a responsibility to regulate the manufacturing industry in order to ensure decent work conditions, the absence of hazardous substances in manufacturing, the minimal consumption of water, electricity and other resources in the manufacturing process, and that there is no environmental pollution in the manufacturing process. Manufacturers have a responsibility to properly respond to these regulations, and to monitor the supply chain for compliance with quality standards, including labour and environmental standards.

Manufacturers also have the responsibility to provide spare parts for longer periods to maximise the durability of their devices, and to allow for software maintenance including security fixes after their own active maintenance period ends. Brands have a responsibility to ensure the recycling and recovery of resources after a device is no longer in use.

Procedures

Commercial brands are sensitive to market forces and their public perception, so lobbying and advocacy for supply chain responsibility can result in indirect demands on technology manufacturing companies. This affects many processes, ranging from the acquisition of raw materials, to manufacturing, packaging and transport, as well as appropriate recycling and reuse of materials.

Amplifying downstream demand for product information and producer responsibility should be promoted through strengthening the expertise of actors within the reuse and recycling ecosystem. This has been done in Finland, among other places.[12]

Information about the chemical and material composition of products is key to protect the health of everyone working with devices. A tax on chemicals used to hold producers financially accountable would establish a clear pathway to finance the control and regulation of toxic chemicals and waste. This is advocated for by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) and International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN).[13]

The importation of devices is a responsibility of customs agencies who can include circularity criteria for imports and introduce taxes to incentivise circularity or compensate for the negative effects of digital devices in their country of destination. Examples of regulatory measures and requirements across borders are compliance with environmental and labour standards, extended producer responsibility, approval for specific types of devices only, mandatory impact assessments, and mandatory traceability of devices.

Global and regional ratings for recyclability, durability and repairability and standardised methods of assessment can be helpful in establishing these regulations. Preventing the export of new or used digital devices to countries without minimal e-waste regulations is worth considering.

Acquisition and procurement

Goal and targets

The acquisition of devices is key for the whole supply chain. The related decisions must be made not only in terms of performance and cost limits, but also with an awareness of the social, economic and environmental effects and limits in the supply chain. If we buy a digital device, we implicitly approve of and support the decisions of the supply chain.

Responsibilities

Acquisition entails decisions where choice gives buyers the opportunity to demand information and compliance with labour and environmental quality requirements and promote good behaviours in the supply chain.

Procedures

Procurement should be guided by the principle of balancing the “right thing” with the “right way”. The right thing is to get the best value for money when purchasing a digital device, while the right way is to do this without a negative impact on communities, workers or the environment.

Responsible public procurement includes ensuring the right of access to devices discarded by a public administration, which were purchased with public money. These devices cannot be recycled prematurely or given away to manufacturers to prevent reuse. This can be implemented in the form of clauses in public procurement contracts and automatic disposal agreements to non-profit reuse circuits upon end of use. An initiative working in this direction is the European Commission’s recommendations on public procurement for a circular economy.[14] The Barcelona City Council is a good example of an institution that has collaborated with reuse circuits. The contribution of the council is not only in the donation of unused computers, but also through promoting demand by using sustainable public procurement.[15] Should countries or regions want to develop socially responsible public procurement processes, a first step is to try to set up “buying clubs”, more formally known as procurement consortia.[16]

Setting up procurement consortia can help by aggregating purchasing power to place demands on suppliers so that labour and environmental rights are respected in manufacturing processes.

The demands from public procurement and procurement consortiums have a knock-on benefit for the everyday consumer, because changes in manufacturing processes will apply to retail products, too.

There may be a need for new criteria to be developed for auditing processes in procurement practices to ensure that public procurement complies with a set of environmental and human rights standards in product purchasing decisions.

Responsible public procurement can be combined with sustainable investment practices by public investors (e.g. pension funds) to strengthen their leverage when engaging with the manufacturing industry.

Public taxes should incentivise the circular economy. Tax incentives for options such as rental, rent-to-own or rental purchase, leasing and pay-per-use instead of purchase should be explored.

Taxation can also have negative environmental consequences. Some examples are given below.

Value-added tax (VAT) favours purchase: While in a linear economy, the full product value is paid upon sale, in circular models, revenue will be obtained over a longer period of time. According to a study on policy measures needed to promote circular revenue models:

Under the current tax regime […] producers operating rent-purchase relationships with customers still need to pay VAT on all projected revenues obtained during the rental period, as rent-purchase is seen as a deferred supply of a good.[17]

VAT favours new products: VAT may be paid more than once for second-hand or recycled products if they are taxed in the same way as new products in every transaction involving the product. As the same study points out:

To stimulate use of second-hand, refurbished, remanufactured or recycled products, VAT could be excluded or significantly decreased for product (parts) that have already been sold once. To make this work, information on product properties, among which the ratio of new versus reused components and materials, is essential in order to achieve this, e.g. by using material passports.[18]

Servitisation, as discussed in Module 8, shows that in some cases, procurement can be implemented as a service contract for a number of computing units with certain capabilities instead of entailing “ownership” of the devices themselves. This is one way to avoid the negative environmental impacts of VAT tax regimes that favour the purchasing of new products.

Footnotes

[1] Ostrom, E. (2009). A Polycentric Approach for Coping with Climate Change. The World Bank. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1494833; see also Finlay, A. (Ed.) (2010). Global Information Society Watch 2010: ICTs and environmental sustainability. APC & Hivos. https://giswatch.org/en/2010 and Finlay, A. (Ed.) (2010). Global Information Society Watch 2020: Technology, the environment and a sustainable world: Responses from the global South. APC & Sida. https://giswatch.org/2020-technology-environment-and-sustainable-world-responses-global-south

[2] Raworth, K. (2012). A Safe and Just Space for Humanity: Can we live within the doughnut? Oxfam. https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/a-safe-and-just-space-for-humanity-can-we-live-within-the-doughnut-210490

[3] Interreg Europe Subtract. (2020). Good Practices. Newsletter #2. European Union. https://www.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/tx_tevprojects/library/file_1595484272.pdf

[4] European Commission. (2013, 8 July). European resource efficiency platform pushes for 'product passports’. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/ecoap/about-eco-innovation/policies-matters/eu/20130708_european-resource-efficiency-platform-pushes-for-product-passports_en

[5] Roura Salietti, M., Flores Morcillo , J., Franquesa, D., & Navarro, L. (2020). Reusing computer devices: The social impact and reduced environmental impact of a circular approach. In A. Finlay (Ed.), Global Information Society Watch 2020: Technology, the environment and a sustainable world: Responses from the global South. APC & Sida. https://www.giswatch.org/node/6270

[6] Wilts, C. H., Bahn-Walkowiak, B., & Hoogeveen, Y. (2018). Waste prevention in Europe: Policies, status and trends in reuse in 2017. European Environment Agency. https://doi.org/10.2800/15583

[7] Directorate-General for Environment (European Commission). (2017). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Implementation of the Circular Action Plan. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a3115190-ed26-11e6-ad7c-01aa75ed71a1

[8] European Commission. (2015). Closing the Loop: An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0614

[9] European Commission. (2016). Communication from the Commission – Ecodesign Working Plan 2016-2019. https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/20375

[10] Bovea, M. D., & Pérez-Belis, V. (2018). Identifying design guidelines to meet the circular economy principles: A case study on electric and electronic equipment. Journal of Environmental Management, 228, 483-494. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479718308855

[11] ITU-T. (2020). Recommendation L.1023: Assessment method for circular scoring. https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-L.1023-202009-I/en

[12] Wilts, C. H., Bahn-Walkowiak, B., & Hoogeveen, Y. (2018). Op. cit.

[13] Center for International Environmental Law and International Pollutants Elimination Network. (2020). Financing the Sound Management of Chemicals Beyond 2020: Options for a Coordinated Tax. https://ipen.org/site/international-coordinated-fee-basic-chemicals

[14] European Commission. (2017). Public procurement for a circular economy: Good practice and guidance. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/circular_procurement_en.htm

[15] Roura Salietti, M., Flores Morcillo , J., Franquesa, D., & Navarro, L. (2020). Op. cit.

[16] Electronics Watch. (2020). Public Procurement in Times of Crisis and Beyond: Resilience through Sustainability. https://electronicswatch.org/public-procurement-in-times-of-crisis-and-beyond-resilience-through-sustainability_2579299.pdf

[17] Copper8, Kennedy van der Laan, & KPMG. (2019). Circular Revenue Models: Required Policy Changes for the Transition to a Circular Economy. https://www.copper8.com/en/circulaire-verdienmodellen-barrieres

[18] Ibid.

No Comments